ex oriente by Gunter Herbig

Ex Oriente – A Musical Journey to Inaccessible Places

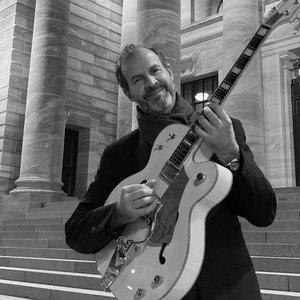

Every journey begins with a single step, or so they say. Other journeys start with a trip to the other side of the world. When I packed up my worldly belongings to emigrate from Germany to New Zealand thirty years ago, a friend gave me a tape with some piano music by George Ivanovich Gurdjieff and Thomas de Hartmann as a going-away present. That tape became an important part of the soundtrack to my discovery of my new home country as I drove around the mountains of the Coromandel Peninsula, the Hauraki Plains and Northland. I thought right away that this haunting and beautiful music would sound wonderful on the guitar, a thought that would follow me and spark my imagination for many years to come.

When I was a teenager, trying to make sense of life and how spirituality could be a compass through the uncharted waters that lay ahead, my mother gave me a book on the teachings of Gurdjieff and a lifelong fascination with him began. I em barked on a career as a university classical guitar teacher and performer, following the footsteps that my guitar heroes and teachers had left in the sand.

As anyone who delves into Gurdjieff’s teaching will know, the realisation that nothing moves in straight lines never takes long to establish itself. Mr G, as he was often affectionately referred to by his closer followers, said himself: ‘without struggle, no progress and no result. Every breaking of habit produces a change in the machine.’ My numerous attempts at transcribing this music for the classical nylon-string guitar (including 10-string and even 12-string alto guitars) always ended in frustration and throwing in the towel. My attempts to shift this music from the piano to the guitar were like water running off the proverbial duck’s back. It was not until a few decades later, after crossing a few valleys and mountains in my life, that I was forced to wake up, and think outside the box in the form of my con ventional classical approach to music in general and the guitar in particular. My ‘machine’ started to engage in the necessary change to make another attempt – this time with a Gretsch ‘White Falcon’ on my lap plugged into a Fender amp. And everything changed, like magic – what always seemed impossible, and a poor approximation of the piano sound and texture on the classical guitar, all of a sudden worked effortlessly and flowed like a river down a pre-ordained course. Finally this music fitted the guitar, as if it had been there all along waiting for me.

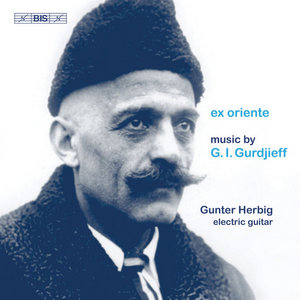

G. I. Gurdjieff (1866/77 (?)–1949) was born into the ethnic and cultural melting pot of Alexandropol on the border of Russian Armenia and Turkey as the eldest son of a Greek Ashokh (bard and story teller) and an Armenian mother. The legends, philo sophical and religious themes his father would recite laid a deep foundation of curios ity and enquiry concerning the everlasting questions about spirituality in young George’s mind. As a young man, he would go on to travel east as far as Tibet, Afghanistan and Central Asia with a group of fellow Seekers of Truth hoping to find answers to the questions of who we are, where we are going and how we are going to get there. During these travels Gurdjieff visited ancient temples and learned from spiritual teachers, absorbing music from all the places he visited. Upon his return to the West, he gathered a group of followers who were drawn to his charis matic personality and his authoritative teaching.

Thomas de Hartmann (1885–1956), a pianist as well as a successful and cele brated composer in his native Russia, was part of this group of followers from 1916 to 1929. A unique collaboration between de Hartmann and Gurdjieff ensued which would produce a staggering body of work: well over 300 piano pieces, fragments for a ballet and music that was to be used as part of exercises for Gurdjieff’s teach ing. De Hartmann, a seeker of artistic truth himself, had been part of the avant-garde movement Der Blaue Reiter (along with Arnold Schoenberg), founded by Franz Marc and Wassily Kandinsky in search of a common spiritual basis of artistic expression. Working with Gurdjieff was a logical step on his own path towards dev eloping his true inner self. De Hartmann describes his first musical encounter with Gurdjieff in his book Our Life With Mr Gurdjieff as follows: ‘In the evenings, he came with a guitar and would play, not in a usual manner, but with the tip of his third finger, as if playing a mandolin, slightly rubbing the strings. They were only melodies, rather pianissimo hints of melodies from the years when he collected and studied the ritual movements and dances of different temples in Asia…’ The fact that Gurdjieff played the guitar, however unconventionally, seemed to me like a sign that my own hunch that this music could be rendered successfully on the guitar was not too far off the mark.

Gurdjieff and his followers eventually settled at the Château Le Prieuré at Fon taine bleau-Avon outside Paris where he established a teaching centre called the ‘Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man’ which would draw a wide range of students from around the world, among them the New Zealand writer Katherine Mansfield.

De Hartmann describes his musical collaboration with Gurdjieff: ‘I had a very difficult and trying time with this music. Mr Gurdjieff sometimes whistled or played on the piano with one finger a very complicated sort of melody – as are all Eastern melodies, although they seem at first to be monotonous. To grasp this melody, to transcribe it in European notation, required a tour de force.

‘How it was written down is very interesting in itself. It usually happened in the evening, either in the big salon of the château or in the Study House. From my room I usually heard when Mr Gurdjieff began to play and, taking my music paper, I had to rush downstairs. All the people came soon and the music dictation was always in front of everybody.

‘It was not easy to notate. While listening to him play, I had to scribble down at feverish speed the tortuous shifts and turns of the melody, sometimes a repetition of just two notes. But in what rhythm? How to mark the accentuation? There was no hint of conventional Western metres and tuning. Here was some sort of rhythm of a different nature, other divisions of the flow of melody, which could not be inter rupted or divided by bar-lines. And the harmony – the Eastern tonality on which the melody was constructed – could only gradually be guessed…

‘When I began the work of harmonizing the melodies, I very soon came to under stand that no free harmonization was possible. The genuine true character of the music is so typical, so “itself”, that any alterations would only destroy the abso lutely individual inside of every melody.

‘Once Mr Gurdjieff said to me very sharply, “It must be done so that every idiot could play it.” But God saved me from taking these words literally and from har mon izing the music as pieces are done for everybody’s use. Here at last is one of the exam ples of his ability to “entangle” people and to make them find the right way them selves by simultaneous work – in my case, notation of music and at the same time an exer cise for catching and collecting everything that would be very easy to lose.’

It was really thanks to the immaculate musical instinct and selfless personality of Thomas de Hartmann that the deceptive simplicity of Gurdjieff’s melodies and rhythms were not over-layered by European art music sentiment and embellish ments. De Hartmann’s purity of style and minimalism gave Gurdjieff’s musical dic tations just enough substance to make them stand as solo piano pieces without giving in to the temptation of showing off his own considerable skills as a pianist. That restraint and their almost ‘guitaristic’ texture opened the door for these pieces to be transcribed to the guitar. Gurdjieff/de Hartmann’s collaboration started with Gurdjieff’s strummings on a guitar, defining the nature of their musical language for the thirteen-year duration of their work together. Returning this music to the guitar thus completes the composers’ journey and returns the music to its starting point.

On another level, my reinvention of this music on the electric guitar is the result of a ‘changed machine’, a changed vision of re-interpreting classical music in a very un-classical medium.The selection of transcriptions on this recording was taken from Schott’s edition – Volumes II – IV of Gurdjieff/de Hartmann’s compositions – works originating in Fontainebleau in the 1920s. Volume II comprised the music of the Sayyids and Dervishes and reflects most characteristically the musical idiom of the Middle East and impressions of Gurdjieff’s travels in his younger years. Sayyids are con sidered to be direct spiritual descendents of the prophet Mohammed and are held in high regard in the Muslim world. While there is no music that can be directly attributed to them, Sayyid Chants and Dances 9, 29 and 42 are evocative of the music of the Mevlevi Dervishes who use chants and dances as a way to reach an ecstatic state.

The compositions in Volume III (Hymns, Prayers and Rituals) reflect Gurdjieff's depth of inner feeling and profound spirituality; they are his subjective expression of another world. While Prayer and Meditation are self-explanatory, Reading from a Sacred Book is reminiscent of a Sayyid chant where a pedal-point tremolo supports a searching, unharmonized melody, improvisatory in style and free in rhythm. The Storm Seemed Over and The Resurrection of Christ are deeply felt meditations on a state of feeling rather than programmatic in nature. As the editors of the Schott edition say about Molto lento e liberamente (No. 11 in the published volume): ‘In some ways the most mysterious composition in this volume may be No. 11. It is almost not music, more like a statement of the soul. This is a page of un compromising objectivity and starkness, an unadorned skeleton.’ The haunting oddness of its harmonic minor intervals and its irregularity of rhythm create an elusive and inward-looking atmosphere of great depth.

The remaining transcriptions were taken from the ‘Selected Works’ section of Volume IV. The Fragments from ‘The Struggle of the Magicians’ are sketches for a proposed ballet that Gurdjieff and de Hartmann worked on during their early asso ciation in Russia. The ballet was never finished but the plot describes a young, wealthy and jaded man’s attempt to win a beautiful girl’s attention. She is a disciple of a ‘white magician’ and devoted to the spiritual path. Unable to gain her interest, the young man engages the services of a 'black magician' to help him to win her heart. The Bokharian Dervish, Hadji-Asvatz-Troov is unique in Gurdjieff/de Hart mann’s oeuvre in that the harmony is entirely European, the only hint at Eastern music being the drone tremolo in the bass. The Bokharian Dervish is an important character in Gurdjieff’s book All and Everything: Beelzebub’s tales to his Grandson in which he describes a number of far-reaching explorations in the realm of sound and vibration, an important part of Gurdjieff’s teachings.

© Gunter Herbig 2018

Gunter Herbig was born in Brazil and grew up in Portugal and Germany. In fluenced by such different cultures and aesthetic languages, he has developed a highly personal, charismatic and expressive style of playing and performance, which sets him apart from his contemporaries. The balance of Brazilian sensuous ness, intense Portuguese passion and German intellect and finesse are the hallmark of his playing. His performance and interpretation philosophy centres on the per sonal and subjective approach to music as a direct way to create a connection be tween the composer, the performer and the audience, and focuses on a sense of musical adventure and exploration. His dynamic and expressive sense of adventure has made him an audience favourite on the concert platform wherever he goes and has solicited universal praise from critics in the international music world. In his distinguished teaching career, he led the guitar departments of Auckland Uni versity for over twenty years and was the head of chamber music at the New Zealand School of Music in Wellington.